Cardiothoracic Surgery

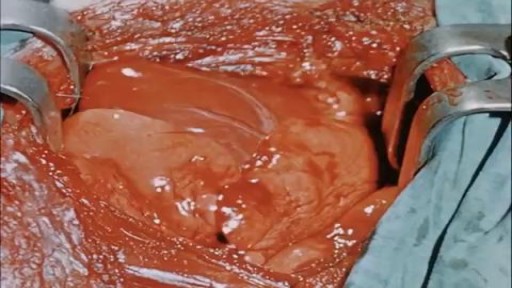

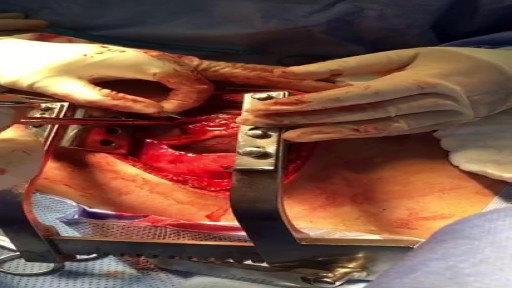

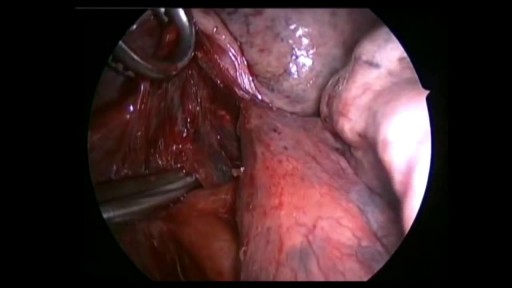

This video is really sad. You can literally watch this man dying. He was shot in the chest and rushed to the emergency room. His heart has stopped beating or has arrested. As a last resort, surgeons did an extreme procedure called an open thoracotomy which is that crazy tool you see there that basically splits the ribs open and allows easy open access to the heart. They did this so they could give him a cardiac massage. A cardiac massage is when surgeons are manually trying to pump the heart after it has stopped working on its own (cardiac arrest). Unfortunately he lost so much blood from his gun shot wound and he was pronounced dead. There are cases of patients surviving after having this kind of invasive resuscitation but it is rare.

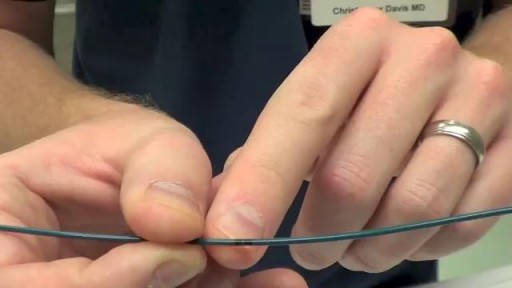

Transvenous cardiac pacing, also called endocardial pacing, is a potentially life saving intervention used primarily to correct profound bradycardia. It can be used to treat symptomatic bradycardias that do not respond to transcutaneous pacing or to drug therapy.

In emergencies (eg, asystole), transcutaneous pacing should be tried first. If transvenous pacing is tried, the catheter should be advanced during asynchronous pacing at maximum output until the ventricle has been captured and a palpable pulse is detected in the patient.

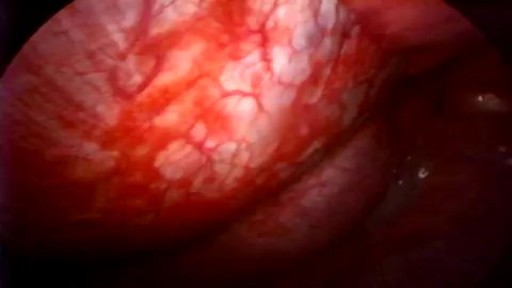

If you have a lung disease, a type of surgery called a lobectomy is one treatment option your doctor may suggest. Your lungs are made up of five sections called lobes. You have three in your right lung and two in your left. A lobectomy removes one of these lobes. After the surgery, your healthy tissue makes up for the missing section, so your lungs should work as well or better than they did before.

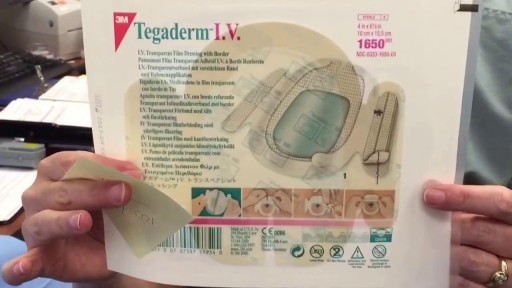

First described by Aubaniac in 1952, central venous catheterization, or central line placement, is a time-honored and tested technique of quickly accessing the major venous system. Benefits over peripheral access include greater longevity without infection, line security in situ, avoidance of phlebitis, larger lumens, multiple lumens for rapid administration of combinations of drugs, a route for nutritional support, fluid administration, and central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring. Central vein catheterization is also referred to as central line placement. Overall complication rates are as high as 15%, [1, 2, 3, 4] with mechanical complications reported in 5-19% of patients, [5, 6, 7] infectious complications in 5-26%, [1, 2, 4] and thrombotic complications in 2-26%. [1, 8] These complications are all potentially life-threatening and invariably consume significant resources to treat. Placement of a central vein catheter is a common procedure, and house staff require substantial training and supervision to become facile with this technique. A physician should have a thorough foreknowledge of the procedure and its complications before placing a central vein catheter. The supraclavicular approach was first put into clinical practice in 1965 and is an underused method for gaining central access. It offers several advantages over the infraclavicular approach to the subclavian vein. At the insertion site, the subclavian vein is closer to the skin, and the right-side approach offers a straighter path into the subclavian vein. In addition, this site is often more accessible during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and during active surgical cases. Finally, in patients who are obese, this anatomic area is less distorted.

Pericardiocentesis is the aspiration of fluid from the pericardial space that surrounds the heart. This procedure can be life saving in patients with cardiac tamponade, even when it complicates acute type A aortic dissection and when cardiothoracic surgery is not available. [1] Cardiac tamponade is a time sensitive, life-threatening condition that requires prompt diagnosis and management. Historically, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade has been based on clinical findings. Claude Beck, a cardiovascular surgeon, described 2 triads of clinical findings that he found associated with acute and chronic cardiac tamponade. The first of these triads consisted of hypotension, an increased venous pressure, and a quiet heart. It has come to be recognized as Beck's triad, a collection of findings most commonly produced by acute intrapericardial hemorrhage. Subsequent studies have shown that these classic findings are observed in only a minority of patients with cardiac tamponade. [2] The detection of pericardial fluid has been facilitated by the development and continued improvement of echocardiography. [3] Cardiac ultrasound is now accepted as the criterion standard imaging modality for the assessment of pericardial effusions and the dynamic findings consistent with cardiac tamponade. With echocardiography, the location of the effusion can be identified, the size can be estimated (small, medium, or large), and the hemodynamic effects can be examined by assessing for abnormal septal motion, right atrial or right ventricular inversion, and decreased respiratory variation of the diameter of the inferior vena cava

Spontaneous pneumothorax is a life-threatening condition in patients with severe underlying lung disease; thus, tube thoracostomy is the procedure of choice in SSP. Pleurodesis decreases the risk of recurrence, as does thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to excise the bullae

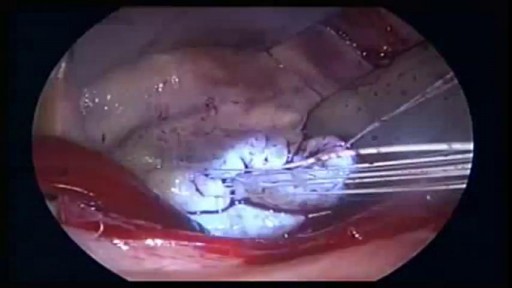

Pericardial window is used diagnostically and, more often, therapeutically for drainage of accumulated pericardial fluid (a condition that most often occurs after cardiac surgery but has many other possible causes). The pericardium envelops the heart like a cocoon; its cardiac filling can be impaired when this cavity fills with excess fluid. When the limited space between the noncompliant pericardium and heart is acutely filled with blood or fluid, cardiac compression and tamponade may result. Pericardial window in combination with systemic chemotherapy may also prevent accumulation of large fluid volumes in patients with neoplastic pericardial disease. [1, 2] Indications The following are indications for a pericardial window [6] : Symptomatic pericardial effusions Asymptomatic pericardial effusions that warrant a pericardial window for diagnosis Hemodynamically stable patients with an undiagnosed pericardial effusion (a thoracoscopic approach is ideal) Coexisting pericardial, pleural, or pulmonary pathology that requires diagnosis or therapy (a thoracoscopic approach is ideal) Known benign effusions that reaccumulate after aspiration Drainage of a purulent pericardial effusion Early fungal or tuberculous pericarditis in which resection of the pericardium is required to prevent future pericardial constriction Use as part of the mediastinal debridement, in patients with descending mediastinitis

During open-heart valve surgery, the doctor makes a large incision in the chest. Blood is circulated outside of the body through a machine to add oxygen to it (cardiopulmonary bypass or heart-lung machine). The heart may be cooled to slow or stop the heartbeat so that the heart is protected from damage while surgery is done to replace the valve with an artificial valve. The artificial valve might be mechanical (made of man-made substances). Others are made out of animal tissue, often from a pig.

There are several ways to do minimally invasive aortic valve surgery. Techniques include min-thoracotomy, min-sternotomy, robot-assisted surgery, and percutaneous surgery. To perform the different procedures: Your surgeon may make a 2-inch to 3-inch (5 to 7.5 centimeters) cut in the right part of your chest near the sternum (breastbone). The muscles in the area will be divided. This lets the surgeon reach the heart and aortic valve. Your surgeon may split only the upper portion of your breast bone allowing exposure to the aortic valve. For robotically-assisted valve surgery, the surgeon makes 2 to 4 tiny cuts in your chest. The surgeon uses a special computer to control robotic arms during the surgery. A 3D view of the heart and aortic valve are displayed on a computer in the operating room.