Top videos

Nasal polyps are soft, painless, noncancerous growths on the lining of your nasal passages or sinuses. They hang down like teardrops or grapes. They result from chronic inflammation due to asthma, recurring infection, allergies, drug sensitivity or certain immune disorders. Small nasal polyps may not cause symptoms. Larger growths or groups of nasal polyps can block your nasal passages or lead to breathing problems, a lost sense of smell and frequent infections. Nasal polyps can affect anyone, but they're more common in adults. Medications can often shrink or eliminate nasal polyps, but surgery is sometimes needed to remove them. Even after successful treatment, nasal polyps often return.

Squamous cell carcinomas typically appear as persistent, thick, rough, scaly patches that can bleed if bumped, scratched or scraped. They often look like warts and sometimes appear as open sores with a raised border and a crusted surface. In addition to the signs of SCC shown here, any change in a preexisting skin growth, such as an open sore that fails to heal, or the development of a new growth, should prompt an immediate visit to a physician.

How to improve your eyesight at home? Exercising your eyes is one of those simple things that very few people do. However, it can help you maintain excellent vision. Here are 10 exercises that will take you no more than ten minutes to do. You can give them a try right now while watching this video – we are going to do all of them with you! Exercise #1. Blink for a minute. Exercise #2. Rotate your head while staring ahead. Exercise #3. Look to your right and left. Exercise #4. Close your eyes and relax. Exercise #5. Move your gaze in different directions. Exercise #6. Close and open your eyes. Exercise #7. Push against your temples with your fingers. Exercise #8. Draw geometric figures with your gaze. Exercise #9. Move your eyeballs up and down. Exercise #10. Strengthen your eyes’ near and far focusing.

The Ortolani method is an examination method that identifies a dislocated hip that can be reduced into the socket (acetabulum). Ortolani described the feeling of reduction as a “Hip Click” but the translation from Italian was interpreted a sound instead of a sensation of the hip moving over the edge of the socket when it re-located. After the age of six weeks, this sensation is rarely detectable and should not be confused with snapping that is common and can occur in stable hips when ligaments in and around the hip create clicking noises. When the Ortolani test is positive because the hip is dislocated, treatment is recommended to keep the hip in the socket until stability has been established

If you’re like me, you probably hook your chest tube up to a Pleur-Evac, put it on the ground, then back away slowly. Who knows what goes on in that mysterious bubbling white box? Hopefully this will post shed some light. Isn’t this just a container for stuff that comes out of the chest? Why does it look so complicated? It’s complicated because the detection/collection of air and fluid require different setups. Most commercial models also allow you to hook the drainage system to wall suction, so you can quickly evacuate the pleural space. This requires its own setup. Because of the need to juggle air, fluid and suction, the most common commercial system includes 3 distinct chambers. If you were to simplify the device, or build one out of spare bottles and tubes, it might look like this:

The surgical procedure uses your own fat, so it is the most natural way to augment your buttocks. Over the last few years, the buttocks have received more press coverage than ever before. People of all ages and body types are having the Brazilian Butt Lift procedure.

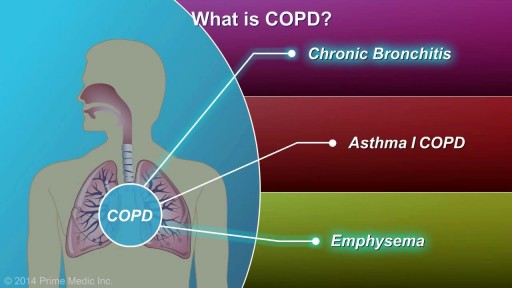

COPD, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is a progressive disease that makes it hard to breathe. Progressive means the disease gets worse over time. COPD can cause coughing that produces large amounts of a slimy substance called mucus, wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and other symptoms. Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of COPD. Most people who have COPD smoke or used to smoke. However, up to 25 percent of people with COPD never smoked. Long-term exposure to other lung irritants—such as air pollution, chemical fumes, or dusts—also may contribute to COPD. A rare genetic condition called alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency can also cause the disease.

To get started, you need to find your pelvic floor muscles by stopping urination in midstream. If you succeed, you have located the right muscles. Once you have located your pelvic floor muscles, tighten the contraction for about 5 seconds, before relaxing for another 5 seconds.